How a costly KPI mistake can impact business success

Authored by JS Irick, Director of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence, TruQua

This is a story about misaligned incentives, business intelligence gone wrong, and how even with the best of intentions, certain KPIs can negatively impact your business. Mostly, this is a story about the 30-minute burrito bowl.

When a surgeon and a consultant get home at 9:30 PM and want a warm, healthy, and above all quick meal, “Tex-Mex Fast Casual” is a tremendous option. Upon arrival at a local eatery, there were a mere 4 people in line. When leaving 30 minutes later with their take-out, that same surgeon and consultant left feeling completely unvalued and unwanted as customers.

So, how did this happen? Let’s start back at the beginning. Fast-casual restaurants work “cafeteria style.” You start your order and then move down the serving line, having your choice of ingredients added to your bowl/burrito/sandwich until you reach the cashier at the end and pay for your order.

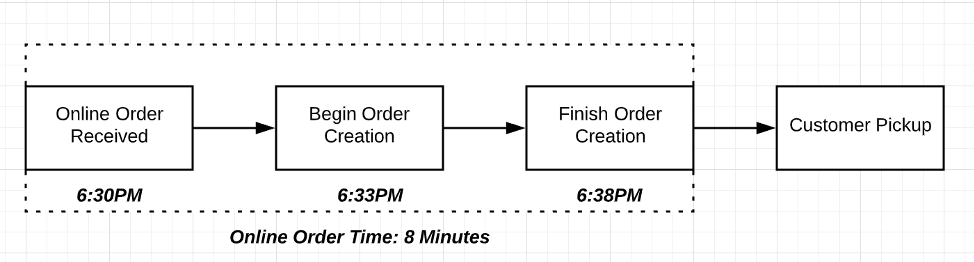

Since its founding, this company has been focused on ways to improve its operations. Gathering customer feedback to optimize the menu, the ingredients, the service, and the cost have been central to their strategy. As a data-focused organization, they have collected customer surveys, average sales, supply chain data, food temperature, etc. But one aspect of their service that they have never had the ability to measure quantitatively is preparation time – the amount of time between the customer beginning their order and when it is actually completed. That is, until the recent advent of online ordering. Online ordering allows the restaurant to track exactly how long it takes for each and every online order that needs to be completed.

So how did this seemingly very positive development lead to a very negative in-person experience? Well, my conjecture is that this company created a KPI (key performance measurement) called Average Online Order Time or something similar. KPIs are an easy way for a business to express operational or financial performance with a single number, and then incentivize it. This is done, for example, with a bonus to the management of franchise locations, such as “If average online order time is under 5 minutes you get a 10% bonus” or something along those lines. Every step of development from the creation of the KPI, to measuring it, to the bonus structure, was created to improve the customer experience. However, something subtle has happened during this process. We have segmented our customer base into those who matter (online orders) and those who do not (in-person orders).

This brings us back to the 30-minute burrito bowl. During the process of ordering, work on the in-person order was halted multiple times while customers watched and waited for online orders to be processed and advanced through the line ahead of their own.

When the online orders were not moving fast enough, the manager stepped in, threw on some gloves, and started working the line presumably to keep the Average Online Order Time within the limits of their incentivized bonus. By the time the in-person customer orders were finished, the four-person line had grown to 25 grumbling, frustrated individuals while a dozen online orders had been completed for unseen customers. The message had been received loud and clear: some customers take priority, while others do not.

So how can this company achieve the intended benefits from implementing this KPI? The unintended consequences were caused by customer segmentation so that the same visibility for determining in-person order time must be created. Gaining this visibility without disrupting the current order process, so traditional “fast food” ordering, where the whole order is tracked and paid immediately is not an option. One alternative is a nightly analysis leveraging OpenCV or similar object tracking technology to determine both time in line and order time. Another is to install a simple IoT button that can be pressed at order start time. These are both more challenging than collecting Average Online Order Time but are necessary to avoid the customer segmentation we experienced. Once Average In-Person Order Time is collected, the company can incentivize the treatment of all customers. KPIs are a wonderful way to quickly gain insight and communicate your business’s performance. However, if you are not extremely careful about how you measure and reward performance, you can end up actively pushing away customers even when you have the best of intentions.

About the Author:

JS Irick has the best job in the world; working with a talented team to solve the toughest business challenges. JS is an internationally recognized speaker on the topics of Machine Learning, SAP Planning, SAP S/4HANA and Software development. As the Director of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence at TruQua, JS has built best practices for SAP implementations in the areas of SAP HANA, SAP S/4HANA reporting, and SAP S/4HANA customization.

JS Irick has the best job in the world; working with a talented team to solve the toughest business challenges. JS is an internationally recognized speaker on the topics of Machine Learning, SAP Planning, SAP S/4HANA and Software development. As the Director of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence at TruQua, JS has built best practices for SAP implementations in the areas of SAP HANA, SAP S/4HANA reporting, and SAP S/4HANA customization.